REPORT BY JOSEPH LEIB

What you’re about to read will amaze and astound you. More than 40 years after Japan’s cowardly sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, HUSTLER has uncovered unquestionable factual evidence that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt knew almost to the hour when the Japanese assault would begin - and deliberately did nothing to prevent it. In fact, he had been working on his celebrated “Date Which Will Live in Infamy” speech several days before swarms of Jap bombers and fighter planes demolished the U.S. fleet and killed in excess of 2,400 American citizens. Now, for the first time, HUSTLER reveals the incredibly sordid story of how our 32nd President sold his country down the river.

There was an eerie calm over Hawaii that morning. Perhaps it was a silent warning of what was to come. On every prior Sunday, for nearly two months, U.S. Navy carrier-based fliers posing as enemy aviators had conducted mock bombing raids while Army antiaircraft batteries directed simulated fire in defense of the island. Just a week earlier the sky over Oahu has resembled a three-ring circus as Navy planes circled, dove and buzzed the decks of the mighty Pacific Fleet’s warships lying in anchor at Pearl Harbor.

But Sunday, December 7, 1941, was different. With just a few exceptions nearly all the Navy’s and the Army’s aircraft were on the ground. No army gunners were ready at their posts. Not a single Navy reconnaissance plane was in the air. Instead, the fighters, bombers, patrol planes, transports and trainers were carefully lined up on runway aprons - wing to wing, tip to tip, in perfect target position.

The sailors of the fleet were also unaware that the clear blue sky above would soon begin raining death and destruction on their gently lolling ships. Except for the carriers Enterprise and Lexington - which were at sea along with a few heavy cruisers and destroyers - virtually the entire Pacific Fleet was in the harbor.

Curiously, though the USS Ward reported sinking a submarine in the prohibited area off Pearl at 6:45 a.m., no alert was sounded. Instead, each vessel’s crew routinely prepared for Sunday religious services.

Aboard the battlewagon USS Arizona the members of the band were excused from performing at morning muster since they had won second place in a contest the night before. They snoozed contentedly, little knowing that their bunks would soon become their eternal resting place and the ship their tomb.

At 7:50 a.m. swarms of Japanese planes swept over the island. From the north, bombers roared over the Army’s Schofield Barracks and past Wheeler Field toward the fleet. Another force came from the east, attacking Kaneohe Field, then Bellows Field and on to the harbor. From the south a third group of planes pock-marked Hickam Air Field with bomb craters and ignited a chain of exploding U.S. planes before continuing toward the helplessly moored warships.

In rapid succession the battleship USS Utah and the light cruiser USS Raleigh were struck by torpedoes from the diving Japanese planes. A single torpedo crippled both the Oglala and the Helena. Moments later an 1,800-pound bomb penetrated the Arizona’s deck and ignited fuel and ammunition caches below, sending more than a thousand sailors and Marines aboard her to a watery grave.

Wave after wave of Japanese planes descended on the harbor, bombing, strafing and torpedoing their targets. By 11 a.m. the attack was over; only the flotsam and jetsam of a once-mighty fleet was left bobbing in its wake.

A terrible price in lives and equipment had been paid. More than 2,400 men were killed outright or died of their wounds soon after. Another 1,178 were wounded. A total of 18 vessels - eight battleships, three light cruisers, three destroyers and four auxiliary ships - were either sunk or knocked out of commission. Eighty-seven naval aircraft were also destroyed along with 77 Army planes.

Equally devastating, the pride of the U.S. Navy also sank that morning. By contrast, the Japanese lost only 29 planes, one attack submarine and five midget subs in their daring raid.

As news about the attack flashed across the nation, Americans reacted with shock, fear and then rage and anger. Yet, as emotions calmed, the inevitable questions were raised.

How could the Japanese fleet sail across the Pacific without detection? Where did Japan obtain the detailed information about the deployment of U.S. forces on Oahu? Why were our ships and planes lined up so neatly together, inviting attack? How could our fighting forces be caught so off-guard? How could they be taken so totally by surprise?

Today, more than four decades later, some of those questions can now be answered. Most of the players in the tragic drama staged at Pearl Harbor are dead now, their terrible secrets taken with them to the grave. There is little owed to them. A far greater debt must be paid to historical truth.

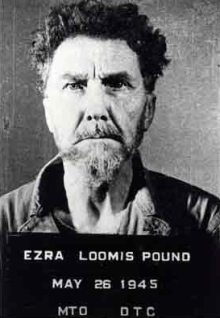

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was hand-correcting a speech he planned to deliver the next evening before a joint session of Congress. That draft is among my most prized possessions. In faded pencil, is the unmistakable scrawl of Roosevelt, inserting a word there, a phrase there.

The next day, the third-term President gave one of his best-remembered addresses. In his lilting, sing-song cadence, Roosevelt called the grieving nation to arms. He labeled December 7, 1941, as “a date which will live in infamy.” His words were so carefully crafted and eloquent, it was difficult to believe he had managed to compose them in the haste and confusion following the attack.

In fact, the treachery of our nation’s leader rivaled that of the Japanese. Roosevelt had labored on the speech for days. He knew well in advance that the Japanese were planning a sneak attack. He knew to the day, almost to the hour, when the assault on Pearl Harbor would begin. December 7, 1941, held no surprises for Roosevelt, nor for me.

A full week earlier, on November 29, I learned about the impending attack from an unlikely source - Cordell Hull, Roosevelt’s own secretary of state. To put the matter into proper perspective, I should explain how and why Hull came to entrust me with the terrible secret of Pearl Harbor.

I arrived in Washington, D.C., on the same train that carried President-elect Roosevelt in March 1933. Though I was only 22 at the time, I moved comfortably within the ranks of movers and shakers who were soon to inherit the reins of government.

My credentials among the Roosevelt crowd were impeccable. I had organized the first Roosevelt for President Club three years earlier in my hometown of South Bend, Indiana, while FDR himself was still running for reelection as governor of New York. By the end of 1930 I was directing active clubs in 21 states.

Prior to the Democratic National Convention of 1932 I convinced House Speaker John Nance Garner to issue public statements that he was not a candidate for the Presidency, and helped head off the “Stop Roosevelt” bloc within the party. As sort of a thank-you, Democratic National Committee Chairman Jim Farley arranged a brief visit with Roosevelt at the governor’s mansion in Albany. At a private meeting with FDR following his victorious election he suggested I select a post in his administration and submit my application directly to him after the Inaugural on March 4, 1933.

Though I had proven my political savvy during the long Roosevelt Presidential campaign, I knew little about the machinery of the government itself. I was caught on the horns of a dilemma. Here I was, presented with an opportunity to pick nearly any job in the administration I desired short of a Cabinet post, and I couldn’t decide. I wanted a job where I could meet people and rub shoulders with the power-brokers, something in public relations.

Finally, a few weeks after he formally took office, I wrote to Roosevelt and asked for an appointment as chief of the passport division under the jurisdiction of the newly appointed secretary of state, Tennessee Senator Cordell Hull. By March 27, Louie Howe, Roosevelt’s closest confidant, had forwarded my request to the State Department, and within a few days Hull himself telephoned to suggest I drop by his office.

Tall and distinguished, with thick-tufted brows poised above kindly eyes, Cordell Hull cut an imposing figure. He had the carriage and bearing of a king; yet he never forgot his Tennessee hill-country origins.

With a sincere twinge of sorrow in his voice Hull explained that the job I sought was held by a career civil servant who could not legally be removed, and asked whether I would be interested in an appointment as special assistant to the woman who currently held the post. After considering his offer for a few days, I thanked Hull for his time and attention but declined the position. The papers were full of rumors of sex scandals within the State Department, and I decided that that agency probably shouldn’t serve as my initiation into government service. My meetings with Hull, however, began a cordial, respectful relationship that was to last throughout his nearly 12 years as secretary of state.

Over the next few years I moved through several of the “alphabet soup” agencies President Roosevelt created to focus government attention on the nation’s depressed economy. At the National Recovery Administration I managed to obtain the participation of the Du Pont Corporation in the NRA’s work. But soon I recognized that the restrictive codes and regulations imposed by the administration were driving small Mom-and-Pop businesses into bankruptcy and launching chains of conglomerates that changed the very face of American retailing.

Next I began handling complaints for the Agriculture Adjustment Administration (AAA) until I witnessed the deliberate slaughter of hogs to keep pork production down. While millions of families starved and begged for food, the government was directing the destruction of crops, dairy products and animals to prop up prices!

I resigned in protest and took a post in the Treasury Department, which wasn’t much of an improvement. As chief of correspondence of the emergency-accounts section in the department’s procurement division, I could watch from a front-row seat while tax dollars were squandered on outrageous programs and federal agencies paid exorbitant sums for equipment that could have been purchased at half the price on the open market.

I argued until I was blue in the face, but it was all to no avail. The fix was in. I finally figured that government service was not for me.

Over the next months I began working as a freelance writer for the New York Herald-Tribune, the Pittsburgh Press and the Paul Block newspaper chain, among others. I also worked for a number of congressmen, writing speeches, handling their public relations and investigating issues.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt was finding that his smooth-sailing ship of state had run into some rough water. The Supreme Court declared both the NRA and the AAA unconstitutional and challenged other parts of Roosevelt’s New Deal program.

Roosevelt, of course, fought back. He began behind-the-scenes maneuvers to purge members of the Senate who opposed his pet projects, and blatantly tried to pack the Supreme Court with justices who would be subservient to his whims. For me that was the last straw. I publicly broke with the President and began directing my efforts against his tyrannical plans.

At the height of the controversy I wrote to Supreme Court Justice James C. McReynolds and questioned him about the rumors circulating in the capital that he intended to retire. McReynolds advised me in his reply to “disregard” all the talk about his resignation, and I leaked the text of the letter to my friend Lyle Wilson, Washington bureau chief of United Press. The story put a damper on Roosevelt’s court-packing plan and spelled defeat for his judicial reorganization proposal in Congress.

Only nine months after FDR took the oath of office for his second term as President, I continued my assault by revealing in the New York Herald-Tribune on October 31, 1937, that Roosevelt was hoping for a war in Europe so that he could sidestep the Constitutional provision limiting a President to eight years in office and seek an unprecedented third term. The story was later reprinted in full in the Congressional Record, only weeks before the election in 1940.

Of course, my organizing activities against Roosevelt earned me his undying hatred, just as my efforts in his behalf a decade earlier had won his friendship. But it was clear he had become a demagogue and wanted to be a sort of king or a president-for-life. I was not alone in that assessment, and my opposition to a third term for Roosevelt also gained for me the fellowship of many politicians and even the grudging admiration of one of Roosevelt’s own Cabinet secretaries, Cordell Hull.

For decades Hull had toiled in service to the nation. He volunteered for duty in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, and upon his return he rode the Tennessee hills as a circuit judge. He was elected to Congress in 1907, and he remained there until Roosevelt beckoned him in 1933.

Between 1921 and 1924 he had paid his political dues serving as chairman of the Democratic National Committee. As secretary of state, he suffered in silence while Roosevelt used Undersecretary Sumner Welles - a closet bisexual - to direct foreign policy from the White House, undercutting Hull at every turn.

At first, Hull had ample reason to be patient. He wanted to be President and told me later that Roosevelt had secretly promised Hull not to seek reelection to a third term. Roosevelt, Hull claimed, had even vowed to support him for the Democratic nomination. But unknown to Hull at the time, FDR had made the same guarantee to a score of others.

Months went by - crucial organizing months - while Roosevelt refused to discuss the issue of a third term publicly. Finally, when FDR made his move, Hull realized he had been betrayed. By the time Roosevelt’s third term ended in 1944, Hull would be 72 - too old, he figured, for a tough race for the White House.

Early in 1941 I came upon some incredible information that, if true, could have badly tarnished Hull’s shining political image. Remembering his personal kindness years before, I wrote to the secretary of state and requested a private audience.

Independently, I managed to confirm the gist of the story that concerted events dating back to the beginnings of Hull’s career in public life. My intention was merely to get a statement from the secretary of state and then publish the story. In a series of meetings over the following weeks Hull acknowledged the truth of what I had discovered.

The scene of our meeting in Hull’s office is still etched deeply in my memory: the courtly secretary of state, hunched over in despair, sobbing and pleading with me to keep the story secret. As Hull related to me the difficult circumstances Roosevelt had placed him in, I began to understand the sorrow and anguish he had suffered. He’d had enough, I decided. I promised Hull never to reveal the information I had obtained, and I have kept that confidence to this day.

Hull told me he never forgave Roosevelt for double-crossing him in 1939; yet he remained in office, cautiously and carefully tying to hold together the fabric of U.S. foreign policy. Hull knew he was the only man in the New Deal Cabinet who had the power and stature to blow the whistle on Roosevelt’s chicanery. But he remained a loyalist for the good of the nation. It was clear that war clouds were on the horizon and that a political crisis in the United States could only benefit the enemies of democracy.

It was in this volatile and uncertain atmosphere that Cordell Hull telephoned me early on Saturday, November 29, 1941, and asked me to see him in person as soon as possible. He wanted to discuss a matter of extreme importance with me, and it was a subject of such sensitivity, it could not be talked about on the phone. There was an obvious note of urgency in his high-pitched voice, and I quickly agreed.

We met outside the State Department (then housed in what is now known as the Old Executive Office Building next door to the White House), and after exchanging brief hellos, walked briskly across the street to Lafayette Park. As we sat on a bench, Hull was fidgeting nervously, betraying the emotions usually masked by his cool demeanor. Suddenly, he burst into tears, and his lanky figure shuddered.

I resisted an impulse to drape my arm around his shoulder and waited patiently for him to regain his composure. Sucking in great gasps of air, Hull began to talk. His words came slowly at first and then fairly streamed from his mouth. It was as if he could barely wait to pronounce them he was so anxious to tell the story.

I could only sit in startled silence as Hull told me Japan was going to attack Pearl Harbor within a few days, and pulled from his inside coat pocket a transcript of Japanese radio intercepts detailing the plan. Recovering from my shock, I began to question him.

“Why are you telling me this?” I blurted out. “Why don’t you hold a press conference and issue a warning?”

“I don’t know anyone else I can trust,” he replied, shaking his head. “I’ve confided in some of your colleagues in the past, but they’ve always gotten me into hot water. You’ve had the goods on me for months; yet you’ve kept your promise not to publish them. You’re the only one I can turn to.”

“Does the President know the Japs are going to attack Pearl Harbor?”

“Of course he does. He’s fully aware of the plans. So is Hoover at the FBI. Roosevelt and I got into a terrible argument, but he refuses to do anything about it. He wants us in this war, and an attack in Hawaii will give him just the opportunity. That’s why I can’t hold a press conference. I’d be denounced by the White House. No one would believe me!”

(Hull’s allegations about FBI complicity in the coverup were confirmed more than a month after Pearl Harbor. A bylined article by United Press reporter Fred Mullen in the Washington Times-Herald declared, “FBI Told Army Japs Planned Honolulu Raid.” The article explained that the bureau had intercepted a radio-telephone conversation on December 5, which mentioned details of the planned raid. Within hours of publication Hoover pressured the newspaper into pulling the story from its later editions.)

After exacting a promise from me never to reveal where I got the document, Hull gave me a transcript of the Japanese message intercepts. I nearly ran the few short blocks to the National Press Building on 14th Street, where I had an office. I took the elevator up to the United Press bureau and brushed past the clerks and reporters into Lyle Wilson’s private office.

Wilson was a longtime friend who had used many of my stories in the past. He was also a chum of Steve Early, Roosevelt’s press secretary; so I swore him to secrecy before I would reveal the purpose of my visit.

I told Wilson I had just left a high governmental official who gave me unimpeachable evidence that Pearl Harbor was about to be attacked and that Roosevelt knew all about it. Wilson was incredulous. He told me my story was simply unbelievable and refused to put it on the United Press wire. Again I made Wilson swear an oath that he would not divulge what I had told him, and I hurried out of his office.

After a frantic series of calls I finally located Harry Frantz, until recently the cable editor of United Press. Harry still had excellent connections at the bureau, and he managed to transmit the story on the UP foreign cable - but not the syndicate’s main trunk line.

Though written in haste, the story as it left Washington contained all the important details of what Hull had confided to me earlier that morning. Yet, somehow, the text was garbled in transmission.

The only newspaper in the whole world to use any portion of the story was the Honolulu Advertiser. A front-page banner headline in the paper the morning of Sunday, November 30, “JAPANESE MAY ATTACK OVER WEEKEND!” A subhead noted, “Hawaii Troops Alerted”.

Suspiciously, the story didn’t mention that the target of the Japanese attack would be Pearl Harbor itself. The horrible cost paid for that simple omission is well-known.

The gloomy news of the calamity at Pearl Harbor descended on Washington like a pall. A couple of days later Lyle Wilson phoned and asked me to come to the bureau. As I walked into his private office, he handed me Roosevelt’s personally edited press release about the “surprise offensive,” saying simply, “I want you to have this.”

“Why are you giving this to me?” I inquired. “It will probably be recorded as the most famous speech Roosevelt ever gave!”

“Steve Early gave it to me,” he replied. “You see, I told him I knew about the attack and didn’t use the story. It was Early’s way of saying thanks. I muffed the most important story of my career. We might have saved thousands of lives.”

Wilson slumped behind his desk and buried his face in his hands. Clutching FDR’s press release, I sat in an empty chair and wept.

See also:

World Jewish Congress FDR & WWII.